Martin Plaut, Author, Unbroken chains: A 5,000 year history of African enslavement

It is a story that should have ended long ago. The abolition of slavery—enshrined in treaties, laws, and global human rights norms—should have been the closing chapter in humanity’s long history of bondage. And yet, in 2025, slavery persists in parts of Africa in brutal, dehumanizing forms. Men, women and children are trafficked, sold, and inherited as property. The suffering is real and ongoing. What is perhaps more shocking, however, is not just that slavery exists—but that powerful regional institutions, notably the African Union and the Arab League, have failed to confront it with the urgency and clarity it demands.

Despite their rhetoric on unity, dignity, and sovereignty, both organizations have proved to be remarkably reluctant to address the reality of contemporary chattel slavery, even when it thrives within the borders of their member states. Whether out of political calculation, denial, or fear of self-implication, the silence from these bodies has contributed to a vacuum of accountability—and allowed the ancient crime of slavery to persist in the modern era.

A Persistent, Evolving Crime

Modern slavery in Africa today takes many forms but includes possibly the most cruel: traditional chattel slavery. It is found in war-torn regions and in relatively stable states, in remote villages and bustling cities. Its essence remains unchanged: the denial of personal freedom and the commodification of human lives.

In Mauritania, one of the most extreme cases, hereditary slavery continues despite legal bans. Members of the Haratin community—descendants of Black Africans enslaved by Arab-Berber populations—still report being treated as property, inherited by masters, and forced to work without pay. While Mauritania criminalized slavery in 2007 and made it a crime against humanity in 2015, enforcement is weak and rare. According to the Global Slavery Index, Mauritania has one of the highest per capita rates of slavery in the world. Survivors who speak out often face retribution or indifference.

In Libya, African migrants are routinely detained, beaten, and sold in makeshift markets by militias and traffickers. Reports by CNN and the United Nations have documented the sale of sub-Saharan Africans for as little as $400. These people are not only denied freedom—they are subjected to rape, starvation, and forced labour under the control of militia factions and criminal gangs. Libya’s collapse into civil war has created a vacuum in which slavery has been revived, often in full view of regional and international actors.

In Sudan, particularly during the decades-long war between the north and south, state-backed militias abducted women and children from communities and held them as domestic and sexual slaves. The violence in Darfur and Sudan’s tragic civil war continues to provide cover for similar abuses.

Elsewhere in West Africa, including Nigeria, Mali, and Niger, extremist groups like Boko Haram and armed militias have used slavery as a tactic of terror—kidnapping girls for forced marriage, conscripting boys into military service, and using civilians for labour.

Institutional Failure

The African Union (AU), established with the mission to promote human rights, peace, and prosperity on the continent, has been conspicuously silent on the issue of modern slavery. While it has a formal commitment to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and has launched campaigns on migration, youth, and gender equality, its response to persistent slavery has been tepid at best.

Take Mauritania, for example. Despite years of documentation by NGOs, human rights observers, and the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, the AU has failed to censure the country or call for serious reform. No sanctions have been issued. No high-level AU delegation has been tasked with investigating or intervening. When African civic groups and former slaves have called for action, but they have been met with repression or silence.

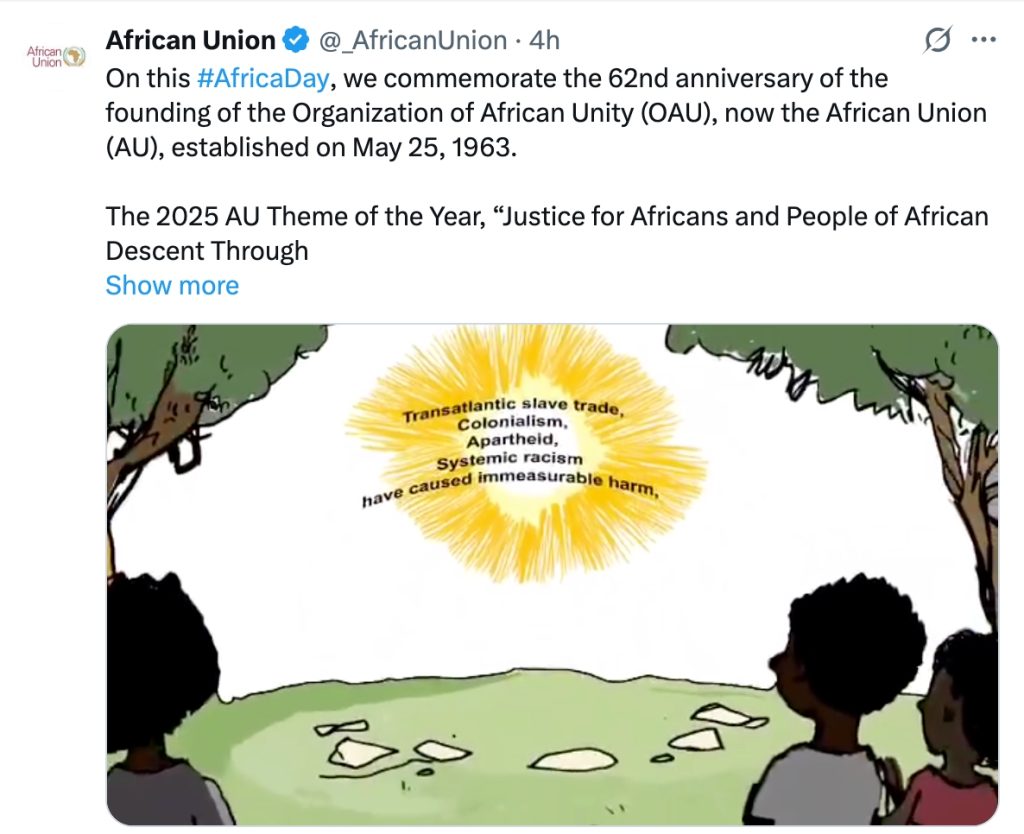

Part of the problem lies in the AU’s principle of non-interference, a hangover from its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity. This norm, originally intended to protect post-colonial sovereignty, has too often served as a shield for governments that oppress their own people. The AU’s failure to act reflects a broader institutional pattern of avoiding internal critique, even when basic human rights are at stake. Instead, the AU concentrates on the history of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, that ended over 150 years ago. Not African slavery so prevalent today.

The Arab League’s inaction is even more pronounced. With member states including Mauritania, Sudan, and Libya—countries where slavery has been practiced openly—the League has never acknowledged, let alone condemned, modern slavery within its borders. The League’s silence is especially egregious given its history and the role that Arab slave traders played in the historical enslavement of Africans for centuries. Today, rather than confronting that legacy and its modern iterations, the League appears intent on ignoring it altogether. Nor has it recognised the role of some of its key members – Egypt or Saudi Arabia – in African enslavement down the centuries.

Erasure, Denial, and Racism

At the heart of this institutional failure is not just political inertia but a deeper reluctance to confront uncomfortable truths about race and hierarchy. In many African and Arab societies, the descendants of slaves remain marginalized, their status entangled with the very social structures that slavery created. Anti-Black racism persists in parts of the Arab world, often rooted in histories of servitude.

This racism is rarely addressed publicly. Schools do not teach it. Leaders do not speak of it. Television and film mostly ignore it. This historical erasure makes present-day slavery easier to ignore. If society does not acknowledge the past, why acknowledge the present?

Moreover, the victims of modern slavery are often the most voiceless—impoverished, undocumented, ethnically marginalized. Their suffering does not command headlines, and their liberation does not serve immediate political goals. Without institutional pressure, governments feel no compulsion to act.

A Moral Imperative

The global anti-slavery movement has made gains—driven by NGOs, journalists, and survivors. But until regional organizations like the African Union and the Arab League acknowledge the scale of the crisis and confront the governments complicit in it, real change will remain elusive.

The AU should launch an independent commission on modern slavery, establish clear enforcement mechanisms, and support civil society actors who are already fighting this battle. The Arab League must break its silence and admit that slavery—historical and contemporary—is not someone else’s crime. It must promote education, reform, and redress.

Slavery in Africa is not just a remnant of history. It is a reality of today. And the institutions created to protect the continent’s people must decide whether they stand for liberation—or for the maintenance of a silence that continues to enslave.